MILLS Wilson VX39238 HQ Coy [A Force]

Pte Wilson MILLS was born on 3 January 1916 in Melbourne. He enlisted on 6 January 1941 and joined the 2/29th on 8 January.

On enlisted he was single, listed Commercial Artist as his occupation and lived in Middle Brighton. Maria Wilson, his grandmother, was listed as next of kin.

Australasian (Melbourne, Vic. : 1864 - 1946), Saturday 24 November 1945, page 16

ART IN THE JUNGLES OF THE EAST

By WILSON MILLS

At the risk of his life, and, as he puts, “to keep going” while labouring as a prisoner of the Japanese on the notorious Burma-Thailand “Death Railway,” Pte Wilson Mills, of Brighton, Victoria, made the sketches published in these pages. Serving with the 2/29th Battalion, AIF, he was captured at Singapore, and in the accompanying article he tells how he did them, and how he concealed them from his guards.

IN THE EARLY DAYS of our captivity in the jungles of Burma, when rations were becoming scarce and life became a bit of a drag, I realised that to keep going under the adverse conditions which were facing us it was necessary to have some occupation which would hold my interest.

On arrival in Mergui, a small fishing village on the east coast of Burma, I was suffering with tropical ulcer which would not allow me to work, so I decided to scout round and see if I could find some materials with which to do some sketches to fill in my spare time.

After much trouble I found a few scraps of old paper, an old pencil (scrounged from the Japanese orderly room when nobody was about), and an old set of water-colours which had been brought from Sumatra by a Dutchman and purchased by me for the sum of 20 rupees.

My first attempts were mainly done from memory, the subjects being chiefly things I had seen in and around the prison camp at Changi. After a few attempts I decided to try my hand at something around me; so came my first landscape drawings from life.

The crowded conditions of our first camp at Mergui, where 1,500 men were quartered in a small two-storey school, made it practically impossible to work, as most of the work was done at night under a very poor light, the object being to work when there was least likely to be any Japanese wandering about the buildings.

I would go out with a scrap of old paper, sometimes no larger than a matchbox, and make a hurried thumbnail sketch of the subject. I would then work on the drawing during the evening, main object being, not a finished drawing but a record which would be valuable for making completed pictures later on.

THE WHOLE IDEA OF DOING the small sketches was not so much for speed as for security! It would have been fatal to have been caught doing these, as the Japanese had issued strict orders that any person in the possession of pieces of paper or pencil would be seriously dealt with. We well knew the meaning of that order from previous experience.

As I finished each sketch I carefully placed it in a length of bamboo and buried it in some safe spot, or hid it in the rafters out of reach of even the most suspicious eyes of our Oriental hosts.

In doing the sketch of the boys working on the aerodrome at Mergui I made the fatal mistake of being a bit too brave, which resulted in my being bashed and having to stand for an hour and a half in pouring rain holding a 15 lb rock above my head.

The Japanese took the sketch from me and threw it away but fortunately did not tear it up. When we were on the road home that evening I noticed that the guard had it in his trousers pocket. Needless to say, that sketch was placed with the rest of my collection that evening and the Japanese was very puzzled as to where his drawing had disappeared to.

After we had been in Mergui for nearly a month, and quite a number had died from dysentery and the almost intolerable conditions, we were moved to a larger and more healthy camp, where things improved consider-ably, and I was able to do quite a lot of work without the worry of the guards catching me un-expectedly, as they had a larger area to look after, thereby allowing me more time between their visits.

Going back a while, I would like to explain the conditions under which the sketches of the hell ship Celebes Maru were done.

We were sailing up the Straits of Malacca on the way from Singapore to Burma, 1,000 men crowded into each of the two holds of the ship, and a menacing machinegun mounted on deck, its glittering barrel trained down upon us.

I managed to get the wrapper from a tin of condensed milk that had been carried by one of the boys, and, getting myself into a convenient corner, managed to do the rough sketch from which the drawing of the interior of the ship was drawn.

The second one was drawn while travelling from the ship to the shore in a Japanese invasion barge.

AT MERGUI, AFTER MOST OF the work on the aerodrome was finished, the Nips took us on what they called sightseeing tours of the town. They were organised, and we went in parties of 200 at a time under a Japanese guard. In the town we were given a fair amount of freedom for a couple of hours-about the only thing decent the Japanese ever did for us-and I was able to do quite a lot of drawings of the village and the Buddhist pagodas around the town.

On this occasion I did not have to hide my efforts, as I was ap-pointed official artist for the Japanese commander in the area. Unfortunately he took most of the drawings before I had time to make copies for myself, and any that I had, except the most important, were later smoked as cigarette paper along the Burma Thailand railway line.

We left Mergui in a small coal vessel known as 593 for Tavoy in August, 1942. We had to wait on the wharf for three days on account of bad weather, and when we did finally get on to the boat we were piled on like a mob of sheep, 300 men in the hold of this 200-ton tub. Conditions were very bad aboard this boat, as loaves of bread they had made at Tavoy about six days before had been lying in the weather on the deck all the time.

We boarded the boat at 4am and tried to settle down for the night, but it was impossible, as we were about three deep on the floor, and everyone was trying to dodge the rain that was pouring in on to us through the open hold. We went on deck the next morning for breakfast, and were handed a small handful of mouldy breadcrumbs. This went on three meals a day for three days, during which time the bread was becoming wetter and mouldier; but it is remarkable how tasty and appetising a handful of mouldy bread can be when there is nothing else.

ON ARRIVAL AT TAVOY on the night of the third day we were transferred to small barges, none too gently, and taken about 20 miles up a large river to the town itself, and on arrival at the wharf were again herded out like a lot of sheep, being driven and cracked with large sticks and being helped along with a decent kick if we were a little too slow in getting off. Two boys were kicked into the fast-flowing river, and it was only with the assistance of the Burmese, who dived in after them, that they were saved.

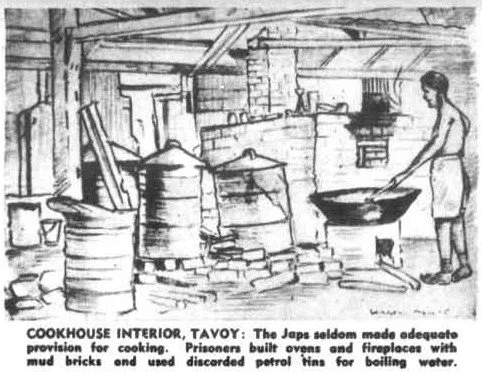

We were billeted in a large school here, and, as the work was not heavy for a while, I had more opportunity, and most of my sketching was done at this camp.

There was also a very sympathetic Japanese sergeant at this, camp, and he became interested in my work when I became bold enough to display it before him.

He had been a Buddhist priest before going into the army, and he did many unusual things to help us, and went as far as protecting us in a big search by the Kempi-Tai, the military police.

I remember him one day sitting in his office crying like a baby, and when asked by our adjutant, Captain Hense, what the trouble was, he said that he had smacked one of the boys across the face, and it was the first time he had ever hit an Australian. He called the chap to his office that evening and sat him down to a big feed, of bread, butter, and cake.

A few days before we left Tavoy for Thambyuzayat and the "Death Railway" he left for Japan, and he sobbed as he came round and shook hands with us all, saying how sorry he felt for us in the work we were about to do. He departed for Japan with quite a lot of sketches of mine as souvenirs, and he is the one Japanese that I hope was not too badly treated in the occupation of Japan.

I had quite a few opportunities of studying the temples and pagodas in this place, and some of them are very remarkable.

Immediately on arrival at Thambyuzayat I was sent on a small job for a couple of days to Moulmein, where I was able to do the sketch of Kipling's "Old Moulmein Pagoda."

FROM THAMBYUZAYAT I was sent to the 26-kilo camp (Kunknitkway), where we first started our work on the railway line. I think the only drawings I did of this camp are now in the possession of Padre Matheson, of HMAS Perth.

It was a very open camp at the end of the valley leading up to the mountains and dense jungle, which was to be our home for the next 13 months. We spent our first Christmas in captivity in this camp, and at the concert which was put on by the boys for the occasion our CO gave a speech which was to inform us that a wireless set had been in-stalled in the camp, and that we would be kept up to date with the news.

His speech was something along these lines: "As you all know, we have a little bird in Australia which is called the nightingale. This little bird sings a very sweet song and a true note. Listen to the song of the nightingale and you will hear its true story. But, remember, the nightingale is a very timid bird. It does not like its nest to be seen by prying eyes, and will not sing its sweet song if its nest is discovered. It will immediately fly away and will be heard no more.

"There is also another bird which is a native of Australia, and the name of that bird is the lyre bird.

"This bird has an exceedingly good and sweet song, but it is not a true song. It imitates and repeats anything that it hears, so that you can never believe its story.

"Therefore do not listen to the song of the lyre bird, but rely on the song of the nightingale. It is a very timid and shy bird, and its voice may be heard every second evening about eight thirty, just as dusk begins to fall.

"Take care that you do nothing to frighten him or try to find where he is hiding, or his voice will cease and he will fly away from you for ever."

THE SPEECH WAS MADE before a large audience of Japanese officers, none of whom was able to make any meaning of the speech; The "Dicky Bird" or "nightingale" was our welcome support for many months to come, and when the Nips would ask us what a nightingale was we would tell them it was a beautiful bird which was a native of Australia, but that there were many of them in the Burma jungle, and that they were only found in or around the prison camps, as they loved Aussies and would only sing for them. They tried for months to hear a nightingale singing, but fortunately they never heard one.

We later went to the 75-kilo camp (Meiloe), and, as the wet season was just setting in, I had enough to do without doing any sketches. Paper was also becoming a very scarce item, and the only paper available was a coarse paper made from rice and bamboo, which at that time was issued to us for latrine use. I have quite a number of notes on this paper that will serve a good purpose in doing my complete collection of sketches.

In doing all these sketches it was necessary to use a certain amount of diplomacy, so I decided that it would be the best policy to leave out any figures, especially of Japanese, from my sketches.

I remember one sketch I did of a number of Japanese guards sitting in their guardhouse. It was really a caricature showing them as I saw them, and I made them half-human, half-monkey. I can assure you it was not a very profitable sketch when one of the Korean guards found it in a search some time later. It was the only occasion that they got hold of my collection through my not taking the usual care and keeping them hidden.

At times when I was too sick to work I used to do quite a bit of portrait work, using my cobbers and the officers as models. I was able to make enough money by charging a dollar a time to keep myself in bananas and the few other things that could be bought, and were vitally necessary to keep me alive. I was also able, through this method, to help my comrades who were sick and dying in the jungle hospital.

OUR NEXT CAMP was at the 105 kilo (Aunggaunuang), where we arrived after a nightmare walk of nearly 30 miles in tropical rain, bare-footed, and most of the time in mud and filth up to our knees. We had to hack our way through dense jungles, getting our meagre clothing soaked.

When we finally arrived at the camp, everything, including our blankets, were wet, and the Nips would not allow us to light fires to dry off. Worst of all, I found that all my sketches, my most precious worldly possessions, were soaking wet. I nursed them all day and at night when the cooking of the meal was finished and it became dark ,I put them in an old tin and dried them by the kitchen fire.

It was while at this camp that the cholera plague broke out so, as I had been given the position of camp bugler, my duties kept me too busy to sketch. I was playing the Last Post as many as eight to ten times each day.

After the plague had passed I again became very sick, and it was at that time that the camp commandant wanted some drawings of the camp. I took the job because it meant a "presento" of some white sugar, salt, a tin of condensed milk, and some badly needed cigarettes.

I was quite surprised to get these, even though I had been promised them, as the officer, Lieutenant Hosie, a Japanese about 4ft 8in and about 16st, was selling all our rations to the natives and leaving us with only dry rice. After the surrender of Japan I had the pleasure of seeing this same officer running around the gaol yard at Bangkok, barefooted, and with nothing to hold up his pants but his hands, at bayonet point; just to take off a bit of his fat. The wily little "Johnny Gurkha" was showing him no mercy. Surely a great sight.

THE WHOLE OF OUR experiences were all such as those described and my poor sketches, which by this time were getting very badly tattered and torn, were going through some terrible times. The latest adventure of them was when we were bombed by a flight of Liberators early this year, and after the raid I found them scattered to the four corners of the camp. This, however, did not deter me. I hunted round and found as many as I could before the Japanese got them, so of the 250-odd sketches I had drawn for my collection only about 50 remained to be brought home.

Surely a terrible catastrophe to so noble an art. I managed to get all these safely through, although I looked as though I might lose them when we were told that we could not take anything back to Australia which might carry disease germs.

I immediately got to work and fumigated them, and eventually talked the health authorities into letting me carry them into the country.