BRYANT-SMITH Stanley QX20748 HQ Coy [F Force]

From The Weekend Australian February 15th 1992

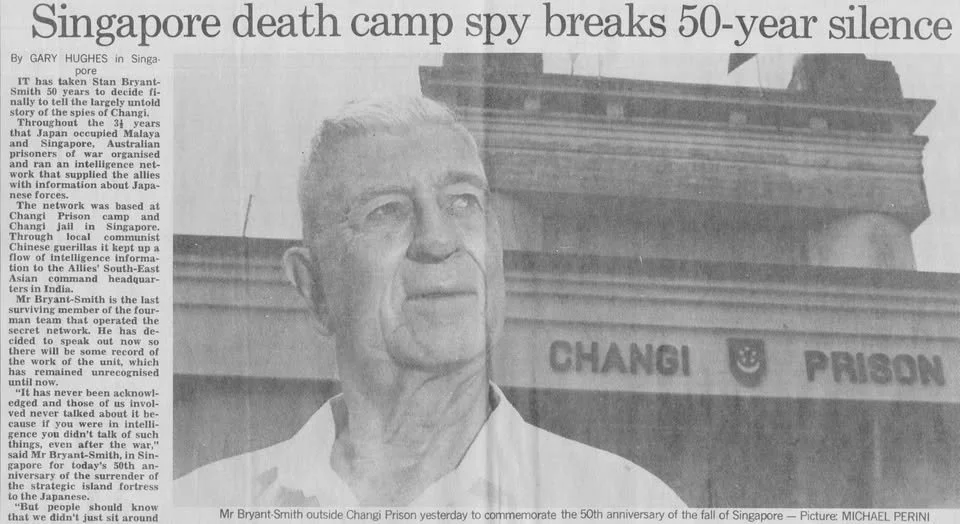

Singapore death camp spy breaks 50 year silence

It has taken Stan Bryant-Smith 50 years to decide finally to tell the largely untold story of the spies of Changi.

Throughout the 3and a half years that Japan occupied Malaya and Singapore, Australian prisoners of war organised and ran an intelligence network that supplied the allies with information about Japanese forces.

The network was based at Changi Prison camp and Changi Jail in Singapore. Through local communist Chinese guerrillas it kept up a flow of intelligence information to the Allies’ South-East Asia command headquarters in India.

Mr Bryant-Smith is the last surviving member of the four man team that operated the secret network. He has decided to speak out now so there will be some record of the work the unit, which has remained unrecognised until now.

“It has never been acknowledged and those of us involved never talked about it because if you were in intelligence you didn't talk of such things, even after the war” said Mr Bryant-Smith, in Singapore for today’s 50th anniversary the surrender of the strategic island fortress the Japanese.

“But people should know that we didn’t just sit around and do nothings as POW’s. We were still fighting the Japs every way we could. We got information out as often we could without ever knowing if it was getting through. It was only after the war we found out that in fact most of it did get through and how useful it was.” Mt Bryant-Smith, now 77 or Penrith in NSW said.

At night time the then Sergeant Bryant-Smith would slip through the barbed wire fence surrounding Changi prison and the camp outside the walls and creep past Japanese guards to reach a small nearby Malayan village.

In the village he linked with an underground unit of the communist Chinese guerrillas, based there specifically to receive information from the prisoners.

The guerrilla group would then use runners to take the information across the island to the Malayan peninsular, where other communist units had radios air-dropped to them by the British.

On one occasion late in the war, POW’s working on the Singapore wharves learned that four huge storage sheds - or godowns as they were known - were packed with Japanese ordnance.

The Australian prisoners passed the information on to Mr Bryant-Smith’s unit and that night word was sent the Chinese guerrillas. “The very next day American bombers came over and dropped dropped incendiaries on the godown numbers 8, 12, 14 and 15 where the ordnance was stored.” Mr Bryant-Smith said.

Mr Bryant-Smith now treasurer of the Eight Division Association and a member of the government liaison committee that helped plan the 50th anniversary celebrations, served with the 2/29th Battalion.

He along with other Australian units, faced the full brunt of the attack by the crack Japanese Imperial Guard on Singapore in the days leading up to the surrender.

He said that on two occasions the Australians turned back the Japanese attack after fierce fighting and he believes they could have been driven off the island. But on each occasion the British High Command ordered the Australians withdraw.

In the final days the Australians gathered at Kanji, now the site of the Allied War Cemetery on Singapore Island ready to make a final stand.

“We hadn’t had supplies or ammunition for three days but we were prepared make a stand and fight and die there.” he said “But the British surrendered.”

In early 1943, Mr Bryant-Smith was one of the 3,500 Australians sent to work on the Burma / Thailand railway with F Force, one of the slave labour gangs.

The were forced to march more than 300 kms into the rugged jungle on the Thai-Burma border where they spent the next eight months working in appealing conditions on a starvation diet.

Disease took an horrendous toll as did the beatings.

Forty-four per cent of those in F Force died on the railway.