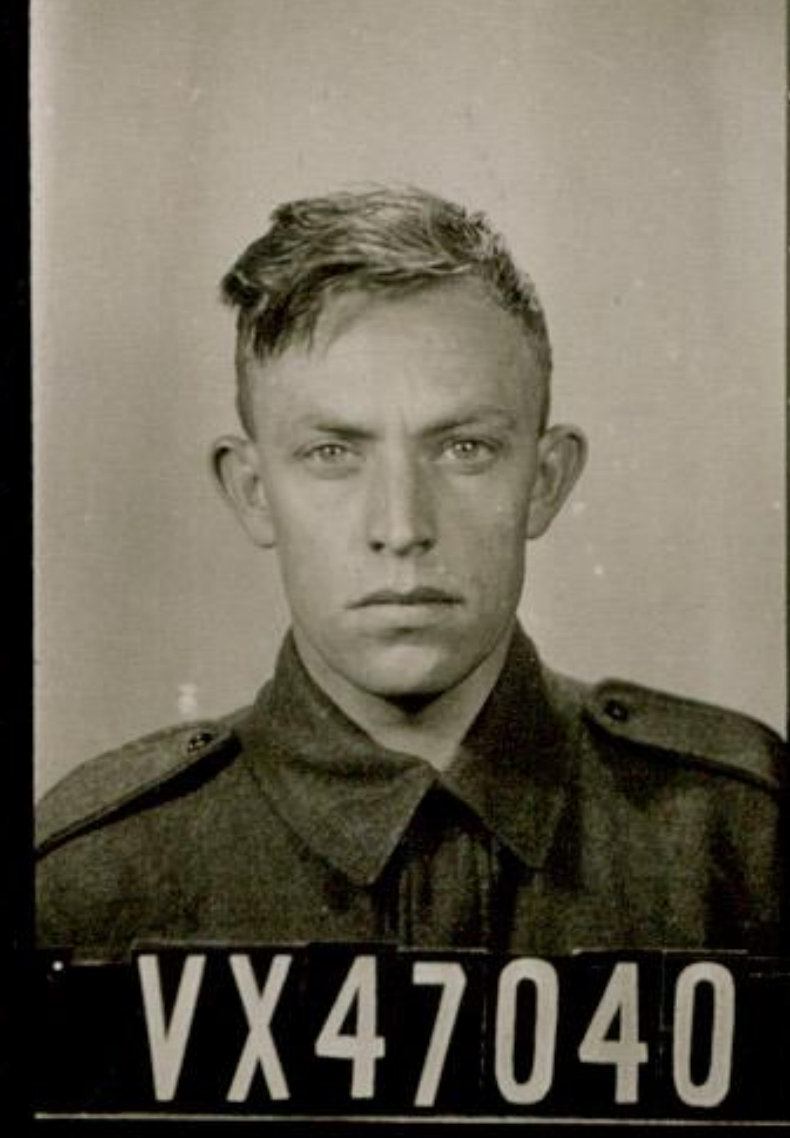

BOEHM, John Wilfred VX47040 B Coy [F Force]

Tribute to Private John Boehm, 1921-2014 2/29th Battalion

Len Boehm

Dad rarely talked about what he went through during the war when we were growing up. All we heard was the light hearted version. We knew about the Japanese Guard who ate a box of laxettes and then disappeared for a week. He told us about a guard who insisted that they would bomb the capital of Australia i.e Canada. We laughed with him as he recalled the Japanese soldier who advised in broken English “you think I know f-nothing when really I know f-all!”. He talked about getting seasick on the way to and from Malaya and swore he would never get on another boat as long as he lived. He even taught us kids to count to 20 in prisoner of war Japanese. Of course we knew something about the war, but the full horror of what happened at Muar and on the Burma railway never came up in detail. Anzac day was a day for dad to sometimes march and see old mates it wasn’t a day for the family to remember. I suspect he didn’t want to burden us with the past.

It wasn’t until many years later when I had children of my own that our connection with the war and dad changed. I was listening to an ABC Radio show called “Australians under Nippon” when dad and mum showed up for a visit. The presenter was describing how the Japanese made thousands of Australians stand in the hot tropical sun at Changi for endless hours and described soldiers collapsing. Dad asked me what I was listening to. I told him and for the first time in my life my dad broke down crying.

Ever since then Anzac day has become the most important event in the Boehm calendar with my brother Bill and I, our wives and as many grandchildren, great grandchildren and assorted hangers on as are available gathering at Barwon Heads to watch the local march, to attend the service and have lunch together. Every year no matter how ill dad was he would march, sometimes standing like a leaf in the wind held up on either side by grandchildren who have also served. This year for the first time he had to be pushed by my brother in a wheel chair. He wasn’t happy.

And a number of traditions developed. Dad would tell us stories from the war reliving the battle of Muar. We knew the story of the gunners and the tanks by heart. Dad’s tattered old pay book that also survived the war would also come out to be carefully passed around like some sort sacred object. He would read the list of his mates in his section and we would all sing his version of an old world war one song he learnt in basic training. We know it as “the lousy lance corporal”.

This song has become an institution in our family. My dad used to sing it to me when I was having a bath as a little kid. I remembered the tune and would sing it to my children and now they sing it to theirs. I remember the shock dad got when he first bathed my girls and they broke into chorus. He just couldn’t work out how they knew a song he sang as a young soldier.

Another tradition would be the attendance of Uncle Leo who served with dad in Malaya and who was his best mate. Leo died a few years ago and I don’t think there was anyone to tell his story, so I will tell it here. Leo was the last wounded man out alive from the battle of Muar and got out of Singapore before the surrender allegedly on the last hospital ship. He escaped with one arm permanently disabled. Some might say he was lucky, but he always suffered survivors guilt, outraged by what the Japanese did to his mates but unable to share in their experience. He never followed up the battalion and rarely marched and mainly kept in contact with my dad. About 10 years ago dad finally talked him into attending a battalion lunch and what followed ranks as one of the most moving scenes of my life. This small, frail old man went up to another frail elderly man, shook his hand and said with much understatement “Doc, you probably don’t remember me, but you saved my life over 60 years ago and I never got the chance to thank you”.

And although Uncle Leo struggled for many years to forgive the Japanese, my dad would never blame them. “Bad things happen in war” he would say, or “they treated their own as badly”. “You don’t blame a people for the sins of their leaders”. Dad didn’t hate.

Like any son of the 2/29th I have since read up on the atrocities the Japanese committed during the war. I’ve read the battalion books and talked things over more and more with my dad. My brother recently asked if I wanted to see a new movie on the Burma rail. I declined telling him I knew enough. But I was wrong. My dad is a gentle reasonable man and even the madness of war was always explained in an understated way.

Dad died after a short illness after seeing his whole family over the last weeks including his 105 year old sister. Most days were pain free and full of laughter, stories and playing of his squeezebox. But on just one day he struggled and he gripped my hand and said “Len I’m not afraid of death but I can’t go through it again. I can’t go through what I went through during the war”. Only in that brief moment as we cried together did I really understand the horror these men went through in the service of their country.

The war does not define my father. He is defined by his love of my mother, by tales of growing up on a farm at Brim, by his roof tiling, by fishing (always from the shore), by dances with mum, by grandchildren, and by the playing of his squeezebox. The miracle was that this good natured young man who went to war in 1940 returned to us. Older with his soul scarred but with his kindness and gentle nature intact.

The 2/29th Battalion Association is the embodiment of the promise that we will always remember. And so I leave you with a promise from my family that we will continue to gather each Anzac day at Barwon Heads to honour their memory and hopefully, for generations to come our decedents will teach their children the song of that young soldier and will pass on the stories of the brave men of the 2/29th.

Lest we forget

Report on John Wilfred Boehm Memoir

By Dianne Cowling

John Boehm, VX47040, was a serving member of the 2/29th and has written his memoirs which also include his early years. John’s great grandparents emigrated from Prussia in 1838 which makes John from a ‘Pioneer’ family. Like many Australian’s of this early time John grew up on a farm in rural Natimuk in Victoria. Also, like many families growing up in the 1930’s, life was hard work without many of the little luxuries we are so used to today. Walking was a way of life as cars were a luxury most could not afford. Hard labour was needed to put food on the table and make ends meet so young men grew up strong of body and able to adapt and do many jobs as it was ‘all hands to the plough’ on a farm. This would stand many in good stead in the hard years as a POW under the Japanese.

When war was declared in September 1939 eager patriotic young Australian men joined up in support of England and Europe being the mother land for many Australians. John’s older brother, Roy, was the first to do so in February 1940 and this encouraged John and his younger brothers to want to do so as well. Three Pound 50 pence per week plus uniform, all clothing and meals was a lot of money then and with the excitement of ‘proving’ themselves as men was too tempting to ignore. As the 2/29th was just being formed in Victoria John was with the first recruits at Caulfield Racecourse where all the enlisted were being gathered from all over Victoria. Like the first of the Battalion John enlisted in July 1940 and he gives some details of his time in training including his time in the Bonegilla Camp near Albury and later Bathurst in NSW before the Battalion embarked for fighting overseas. Training in Australia was in ‘open warfare’ so when the troops landed in Singapore Brig Gen Gordon Bennett knew his troops needed to be retrained in jungle warfare and John gives a detailed account of the time from landing on Singapore Island until finally the enemy is engaged by the 2/29th at the Battle of Muar 17th January 1942. John remembers the fighting but the nightmare trip from Muar back to Singapore “escapes my memory” says John. He has included excerpts from ‘The History of the 2/29th’ and “Percival & the Tragedy of Singapore” by Sir John Smyth VC. John also points to other books that give a lot more detail of this battle as well personal experiences of other men as POW’s under the Japanese. He mentions “Prisoners of the War- Australian under Nippon” by Hank Nelson & 'A Doctors Diary' by Dr Roy Markham Mills.

Once back on Singapore Island John resumes his recollections of the fighting and the ‘surrender’ which left a very bad taste in the mouths of the troops, many of whom wanted to go on fighting rather than give up, but they were trained to follow orders and follow them they did. John talks about his time at Selarang Barracks in Changi Provence before he was finally sent out to work on Thai Burma Railway with many of the 2/29th in F Force on ANZAC day 1943. Pond’s Party F Force had Dr Roy Markham Mills as their ‘force’ doctor and all who survived give credit to this amazing man for what he did for them all. Johns praise for Dr Mills could not be high enough and he goes on to say that “survival was 99% luck”. He remembers the illnesses and diseases that they all suffered, many of his friends never survived but John did and remembers how hard it was adjusting to the diet back home after the depravation of his time as a POW. The Post War period for those who survived saw many of the men suffer reoccurring bouts of the diseases suffered as a POW. John was a true Aussie Battler and never gave up, he married and had two children and continued to work at anything that would put food on the table and pay the bills. Never giving up stood John in good stead and in 1979 after living a good life John and his wife retired to Barwon Heads. John remained involved with the RSL, old time dancing & snooker and his growing family including his grandchildren. The memoirs finish in 1997 with John & his wife happily enjoying their beach change and life in general.